In the wake of October 7th, a seismic shift is occurring within Israel's ultra-Orthodox community. The long-standing exemption from military service for Haredi yeshiva students is facing unprecedented scrutiny – not just from secular Israelis, but from within the Haredi world itself.

This week's Torah portion, Bamidbar (Numbers), offers a timely lens through which to examine this complex issue. As we explore the biblical census and military draft, we uncover surprising parallels to today's debate over Haredi enlistment.

A Biblical Precedent for Sacred Service

The book of Numbers opens with a divine command to take a census of all Israelite men aged 20 and over – those eligible for military service. Yet, amidst this universal draft, we find our first exemption:

(1) On the first day of the second month, in the second year following the exodus from the land of Egypt, God spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai, in the Tent of Meeting, saying: (2) Take a census of the whole Israelite company [of fighters] אֶת־רֹאשׁ֙ כׇּל־עֲדַ֣ת בְּנֵֽי־יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל by the clans of its ancestral houses, listing the names, every male, head by head. (3) You and Aaron shall record them by their groups, from the age of twenty years up, all those in Israel who are able to bear arms. כׇּל־יֹצֵ֥א צָבָ֖א בְּיִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל (Numbers 1:1-3)

(45) All the Israelite males, aged twenty years and over, enrolled by ancestral houses, all those in Israel who were able to bear arms— כׇּל־יֹצֵ֥א צָבָ֖א בְּיִשְׂרָאֵֽל (46) all who were enrolled came to 603,550. (47) The Levites, however, were not recorded among them by their ancestral tribe. (48) For God had spoken to Moses, saying: (49) Do not on any account enroll the tribe of Levi or take a census of them with the Israelites. (50) You shall put the Levites in charge of the Tabernacle of the Pact, all its furnishings, and everything that pertains to it: they shall carry the Tabernacle and all its furnishings, and they shall tend it; and they shall camp around the Tabernacle. (Numbers 1:45-50)

The Levites were set apart for a different kind of service – tending to the Tabernacle and its sacred duties. This biblical precedent has long been used to justify the exemption of yeshiva students from military service. The argument goes: Today's Torah scholars are the spiritual heirs of the Levites, protecting Israel through their study and prayer.

But is this comparison truly valid?

Classical Commentators attribute the Levites exemption to their superior spiritual status..

They were not counted because the charge of the tabernacle was upon them. Therefore they did not serve in the army. (Ibn Ezra)

God now explains that the reason why the Levites were not to be counted with the other twelve tribes was not their ineligibility but on the contrary, it was their superior position which required them to be counted separately. Seeing it was going to be their function to perform all manner of service connected with the Tabernacle, they would be counted separately and would form a separate camp. (Rabbenu Bahya)

But an argument could be made that the fact that they were not allotted a portion in the land created the exemption and conversely, if you are a stake holder, you need to serve.

(6) Moses replied to the Gadites and the Reubenites, “Are your brothers to go to war while you stay here? (7) Why will you turn the minds of the Israelites from crossing into the land that יהוה has given them? וְלָ֣מָּה (תנואון) [תְנִיא֔וּן] אֶת־לֵ֖ב בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל מֵֽעֲבֹר֙ אֶל־הָאָ֔רֶץ (Numbers 32:6-7)

The impact that draft dodgers have on the morale of those that serve sounds very contemporary.

One could also argue that if the Torah wanted to exempt Torah Scholars, it could have done so. It is not as though it does not recognize the concept of exemptions.

(4) For it is your God who marches with you to do battle for you against your enemy, to bring you victory.” (5) Then the officials shall address the troops, as follows: “Is there anyone who has built a new house but has not dedicated it? Let him go back to his home, lest he die in battle and another dedicate it. (6) Is there anyone who has planted a vineyard but has never harvested it? Let him go back to his home, lest he die in battle and another harvest it. (7) Is there anyone who has paid the bride-price for a wife, but who has not yet taken her [into his household]? Let him go back to his home, lest he die in battle and another take her [into his household as his wife].” (8) The officials shall go on addressing the troops and say, “Is there anyone afraid and disheartened? Let him go back to his home, lest the courage of his comrades flag like his. וְלֹ֥א יִמַּ֛ס אֶת־לְבַ֥ב אֶחָ֖יו כִּלְבָבֽוֹ” (Deuteronomy 20:4-8)

Challenging the Status Quo

Enter Rabbi David Leibel, a 70-year-old Haredi leader making waves with his call for ultra-Orthodox enlistment. Educated in the prestigious Ponovezh Yeshiva, Liebel possesses the scholarly credentials to challenge his peers on their own turf.

His provocative statement cuts to the heart of the matter: "If Torah study really protected Israel, October 7th wouldn't have happened."

Check out the full documentary of Leibel by channel 12 in Israel:

Leibel dismantles the traditional arguments for exemption:

1. The "Levite" Argument: He points out that one cannot simply declare oneself a modern-day Levite. Either you are born into that lineage or you're not.

2. Torah Study as Protection: Liebel argues that the Talmudic concept of Torah study offering protection applies to individuals, not entire communities or nations.

3. Preserving Yeshiva Culture: The fear that army service will lead to secularization is countered by the creation of Haredi-specific units with accommodations for religious practice.

A Moment of Reckoning

The events of October 7th have forced a painful self-examination within the Haredi community. Liebel notes that on October 8th, many ultra-Orthodox Jews were eager to help, asking what they could do to support their country.

This internal shift reflects a broader redefinition of what it means to be Haredi in modern Israel. As more ultra-Orthodox youth struggle with unemployment and seek integration into wider society, the army may offer a path to both national service and personal development.

Reframing the Mitzvah of Military Service

It's crucial to remember that serving in the IDF isn't just a civic duty – it's a mitzvah, a religious commandment.

Ben-Gurion argued to the Chazon Ish decades ago, settling and defending the land of Israel are fundamental Jewish obligations….

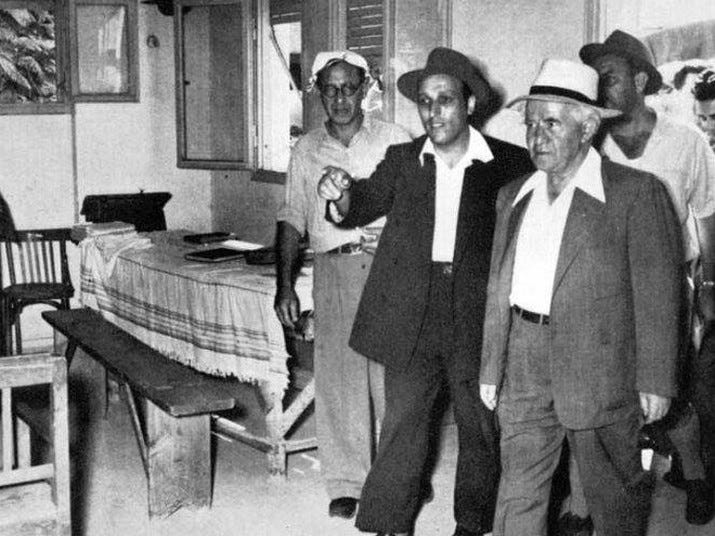

Ben Gurion visits the Hazon Ish - Yizchak Navon, writing sometime later about the meeting, recounted how Rabbi Karelitz, responding to Ben-Gurion’s query regarding “how can we live together,” described a scene from the Talmud in which, when “two camels meet on a path, and one of the camels is weighed down with a load, and the other camel is not, the one not carrying the burden must give way to the one who is.” The moral of the parable, suggested Karelitz, was that, “We, the religious Jews, are analogous to the camel with the load – we carry a burden of hundreds of commandments. You” – secular Israel – “have to give way.”...

Ben-Gurion, according to Navon, attempted to mount a counter-argument. “And the [second] camel isn’t weighed down with the burden of commandments?” he asked rhetorically. “The commandment to settle the land isn’t a burden?... And the commandments to defending life aren’t mitzvot? And what those boys whom you are so opposed to do, sitting on the borders and protecting you, that’s not a mitzvah?”

Karelitz was not even able to agree, according to Navon, that the learners’ lives were protected by those serving in the army. Rather, he insisted that, “It is only thanks to the fact that we learn Torah that they [the soldiers] are able to exist.”

see: When David Ben-Gurion Met the Chazon Ish, The National Library and the NYTimes October 21st 1952 BEN-GURION MEETS RELIGIOUS LEADER

By creating Haredi-specific units and programs, the IDF is working to accommodate religious needs while fulfilling this essential mitzvah. These efforts challenge the notion that army service is inherently at odds with an ultra-Orthodox lifestyle.

The argument made by the Hazon Ish was best summarized by Israel Chief Justice Aaron Barak:

In his 1998 leading decision in Rubinstein v. Minister of Defense on deferment of military service for yeshiva students, Supreme Court President Aharon Barak explained the reason for the deferment and its historical context as follows:

The original reason for the arrangement was the destruction of the yeshivas in Europe during the Holocaust and the wish to prevent the closing of yeshivas in Israel due to their students being drafted to the army. Today this objective no longer exists. The yeshivas are flourishing in Israel, and there is no serious worry that the draft of yeshiva students, according to any arrangement, would bring about the disappearance of this [yeshiva] institution. see Israel: Israel: Supreme Court Decision Invalidating the Law on Haredi Military Draft Postponement March 2012

A Path Forward

The debate over Haredi enlistment is far from settled, but voices like Rabbi Leibel's are opening new avenues for dialogue. As Israel grapples with security challenges and social divisions, finding ways to integrate the ultra-Orthodox into national service becomes increasingly vital.

This isn't just about sharing the burden of defense. It's about forging a more cohesive Israeli society where all sectors contribute to and benefit from the nation's strength and prosperity.

What We've Learned

The Torah's treatment of military service offers enduring wisdom:

- Service is universal: With few exceptions, all able-bodied men were expected to serve.

- Exemptions are specific: The Levites had a clearly defined alternative role.

- Flexibility exists: Deuteronomy outlines various reasons for temporary deferment.

As we navigate this complex issue, let's draw inspiration from our tradition's nuanced approach. The goal isn't to erase Haredi identity, but to find ways for this vital community to participate more fully in Israel's national life.

Call to Action: Listen to the full episode for a deeper dive into this fascinating topic. How do you think Israel can best integrate its ultra-Orthodox population while respecting their unique religious commitments? Share your thoughts and continue this important conversation.

Sefaria Source Sheet: https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/651245

Transcript:

Geoffrey Stern: If Torah study really protected Israel, October 7th wouldn't have happened. That's not a YouTube comment. That's a quote from a prominent Haredi rabbi. For decades, ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel have claimed exemption from military service on the grounds that their Torah learning defends the state. But after the Hamas massacre, the conversation shifted, and some within the Haredi world are no longer staying silent.

Today we're diving into why some tribes were drafted and others weren't, what are acceptable reasons for not serving, and whether the Torah supports the idea of sacred exemption. Because behind the headline debate—should Haredim serve?—lies a deeper question: what does it mean to be a Haredi today?

Welcome to Madlik. My name is Geoffrey Stern, and at Madlik, we light a spark, or shed some light on a Jewish text or tradition. Along with Rabbi Adam Mintz, we host Madlik Disruptive Torah on your favorite podcast platform and now on YouTube. We also publish a source sheet on Sefaria, and a link is included in the show notes. And if you do listen to us on YouTube or a podcast platform and you want to leave a good review or give us a few stars, go ahead and do it.

This week's Parsha is Bamidbar. In English and based on the Greek Arithmoi, it is more properly called Numbers, and it starts with the head count of all able-bodied males over 20 who are all obligated to serve in the army. We explore the texts from the perspective of those so-called ultra-Orthodox who claim exemption from serving in the Israeli army. So join us for "Haredim Enlist."

Well, Rabbi, we are recording on Memorial Day, so I guess there is no better time. In Israel, they celebrated—if that's the right word—Yom Hazikaron a few weeks ago. But obviously, we all have to recognize the sacrifice of those who sacrifice to protect us. And I think it's particularly important in these times.

If you read the press from Israel, this is very live. There are soldiers who have served in the reserves. Israel is a voluntary army. They've served for 240 days, and they're being called back. Some of them are not going back, not because they're conscientious objectors, but simply because they can't; they can't interrupt their life anymore. They're carrying the whole burden. And there's a segment, a large segment, close to 20%, called the Haredim, who aren't serving. So it's becoming a bigger and bigger issue, and I couldn't think of a better Parsha to begin that discussion.

Adam Mintz: I couldn't agree with you more. And this is the issue. And what a good Parsha! The Parsha of Chumash Hapekudim, you had it in the Latin and the Greek. But the book of Numbers, the book of how the Jews traveled and how they served in the army. This is what it's all about.

Geoffrey Stern: So it's called "Haredim Enlist." The word enlist literally means to voluntarily join a cause or organization, especially military service. The word "list" is in there, and that's really what Numbers is. It's a bunch of lists. And we start with the list of Israelites over the age of 20. Bamidbar One says, on the first day of the second month in the second year following the exodus from the land of Egypt, God spoke to Moses in the wilderness of Sinai in the tent of meeting, saying, take a census of the whole Israelite company. My translator puts in parentheses "of fighters" by the clans of its ancestral houses, listing the names, every male, head by head. You and Aaron shall record them by their groups from the age of 20 years up, all those in Israel who are able to bear arms. So it says, "be yisrael tifkedu otam l'tzava otam" and "tzava" is the word in Hebrew that we use for the army, meaning the Israel Defense Forces. Here in the biblical Hebrew is the same word being used. And literally, this is a head count. The Parsha goes on later.

Adam Mintz: By the way, that's interesting that the army is named after "tzivotam," which means their groups. That's just interesting. I mean, that's not an Israeli thing, that the word "Tzava" means army.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah. And I think, again, whether it's a poll tax or a head tax, a lot of these words in not only our tradition had to do with counting people for what was ultimately the most meaningful service that they had to do. Which is, yeah, there might have been taxes at a certain point in time, but what the king did was he gathered together an army. He took the firstborn from every family. So all of these words are kind of related. Later on in our Parsha, in verse 45 in the same chapter, it says all the Israelite males aged 20 years and over enrolled by ancestral house. All those in Israel who were able to bear arms, all who were enrolled came to 603,550.

The Levites, however, were not recorded among them by their ancestral tribe, for God had spoken to Moses saying, do not on any account enroll the tribe of Levi or take a census of them. With the Israelites, you shall put the Levites in charge of the tabernacle of the pact, all its furnishings and everything that pertains to it. They shall carry the tabernacle and all its furnishings. They shall tend it, and they shall camp around the tabernacle. So at the very moment that we list who has to serve, we have our first deferment, if you will. The Levites are not to be counted. And the reason they're not to be counted, it's clear, is because they don't serve in this army, they serve somewhere else also. Kind of. You cannot help but draw some lines to the current conversation, which is if you don't serve in the army, you do need to serve somewhere else. I think that's what they argue.

Adam Mintz: We're the modern-day Levi.

Geoffrey Stern: Yes, and I was going to say that as well. And again, that's an argument that is going to be kind of hard to make. But yes, it's definitely. Just look a little bit at the commentaries. The Ibn Ezra says, but appoint thou the Levites over the tabernacle. Scripture explains here why the Levites were not counted. They were not counted because the charge of the tabernacle was upon them. Therefore, they did not serve in the army. So I think you make a good point that you could say, on the one hand, we have the original listing where the census is on everybody, and there is an exclusion, and that is the Levites who serve in the tabernacle.

The Rabbeinu Bahya says, and you are to appoint the Levites as in charge of the tabernacle of testimony. This whole verse is the explanation of verse 49, in which Moses has been told not to include the Levites in the census for the army. God now explains that the reason why the Levites were not to be counted with the other 12 tribes was not their ineligibility, but on the contrary, it was their superior position which required them to be counted. So here's a commentary on that. I think you could make a very different argument.

The different argument actually comes up much later in the Book of Numbers. And if you recall, the Gadites and the Reubenites, as they approached the land of Israel, said, we want to stay right here. We don't want to cross over the River Jordan. And Moses replied to the Gadites and the Reubenites, are your brothers to go to war while you stay here, will you turn the minds of the other Israelites from crossing into the land that God has given them? So here it becomes—so there's definitely a connection between having a portion in the land of Israel and fighting. And I think it's clear that the Levites, who did not have a portion in the land, they were not allocated in the 12 tribal allocation, didn't have to fight. But again, there were arguments that we're going to come to later on which will say, you know what, if you don't want to fight, that's fine, but then you can’t benefit from some of the rights of being a citizen. Maybe you shouldn't be able to vote and send other people's children to war.

Maybe you shouldn't have money coming in to pay for your schooling and other such things. It's amazing how relevant all of the issues that are being raised in the Torah with regard to the draft are to the present conversation.

Adam Mintz: It really is. Now, that idea that if you don't have a share of the land, you're not going to fight, that's not such a good idea. Meaning when they criticized Gadand Reuven, saying that they'll go to war and you'll stay here because you don't have a share in the land, that's a criticism. So if we say to Levi, you're not going to work, you're not going to fight, sorry, because you don't have a share in the land, that would be a criticism of that.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah, yeah. And I think you can also, the flip side of that is we saw a little bit a second ago in the Ibn Ezra, and that the fact that they didn't have to serve, you could say, was to give them shvakh to say that they were serving at a higher level. I mean, to extend your argument a little bit, also, what do you do to a landless person who maybe sold his piece of land? So there is nothing simple about this discussion. I agree.

But in terms of a deferment, the Torah in Deuteronomy, actually, it's not as though it wasn't aware that not everybody is gonna go. In Deuteronomy 20, it says, "for it is your God who marches with you to do battle for you against the enemy, to bring you victory. Then the officials shall address the troops as follows. Is there anyone who has built a new house but has not dedicated it, let them go back to his home, lest he die in battle. And another dedicated it. Is there anyone who has planted a vineyard but has not harvested, let him go back to his home lest he die in battle. And another harvest? Is there anyone who has paid the bride price for a wife, but who has not yet taken her. Let him go back to his home." The officials go on addressing the troops and say, "is there anyone afraid and disheartened? Let him go back to his home, lest the courage of his comrades flag like his."

So I also could make the argument, Rabbi, that because the text of the Torah was not blind to the fact that there were some people who were either not able-bodied enough to serve or who had other reasons for these exceptions are, they did make some exceptions. But I think if you're going to get back to the Haredim, ultra-Orthodox, saying that they are the Levites, it doesn't say if you're a teacher, it doesn't say if you are a Levi wannabe. It talks about serving in the Torah. So I do think it's a little bit of, I would say, a chutzpah for someone to argue when it comes to a halacha like this, because it actually is a rule that we should be considered like a Levi. You know, you can't make that argument when it comes to getting an aliyah on Shabbat. Either you are a Levi or you're not a Levi, either you serve in the Temple, or you don't serve in the Temple. So it's all very fascinating.

Adam Mintz: Good. I mean, that introduces the idea of arrogance in this whole thing. Who are we to say that we're Levites?

Geoffrey Stern: Absolutely.

Adam Mintz: Who's to say that our Torah study in Yeshiva is the equivalent of the Levite who works in the Temple? That's right. That's interesting. I mean, they don't make a big point about that, but that's a very important point.

Geoffrey Stern: Okay. I think that is an amazing segue to the little quote that I'm. Now we're going to come up into the present tense. And the present tense. In 1998, there was actually an adjudication in the Supreme Court in Israel regarding the deferment of military service for Yeshiva students. And the Supreme Court president was Aaron Barak. And he explained what the original reason was for the Yeshiva students not

Geoffrey Stern: to go to the army. And this is a quote from his legal background, his context. "The original reason for the arrangement was the destruction of the yeshivas in Europe during the Holocaust and the wish to prevent the closing of Yeshivas in Israel due to their students being drafted to the army." He says today this objective no longer exists. The Yeshivas are flourishing in Israel and there is no serious worry that the draft of Yeshiva students according to any arrangement would bring about the disappearance

Geoffrey Stern: of this Yeshiva institution. So we're going to go back a little bit in history, and this Aaron Barak context serves as to what happened in the early days of the state of Israel when they were discussing these issues. And I think if you had to go to one moment, and I'm showing a picture of it, if you're listening to the podcast and not seeing anything, you can look at the Sefaria sheets. But it's a picture of David Ben Gurion entering the house of the

Geoffrey Stern: Chazon Ish. The Chazon Ish was the great halachic adjudicator of what became the Haredim. He was (Ben Gurion was) accompanied by a partner or a secretary or a sidekick named Yitzhak Navon, who ultimately became the president of Israel, but was a very knowledgeable traditional Jew. And so while there was no recording of the meeting, what seems to have happened is that Ben Gurion

Geoffrey Stern: came in and said, how can we live together? And the first famous thing that the Chazon Ish told him was he gave him the story of the two camels. Actually, it's from the Talmud, and in local nomenclature in Israel now, it's called the story of the two Wagons. If two wagons are on a narrow road, which one gets precedence? The Talmud says, the one that has a full load, as opposed to the empty wagon or camel. So the Chazon Ish turns to Ben Gurion and

Geoffrey Stern: he says, we, the religious Jews, are analogous to the camel with the load. We carry a burden of hundreds of commandments. You, secular Israeli, have to give way. You, secular Israel, have to give way. Meaning to say that we're doing all the learning, we have all the mitzvahs. You have an empty cart. Ben Gurion was not a soft pushover, and he was not there as a secular Jew. He was there as a Jew who was starting the land of Israel. So Ben

Geoffrey Stern: Gurion, according to Navon, attempted to mount a counter-argument. And the second camel isn't weighed down with the burden of commandments. He asked rhetorically. The commandment to settle the land isn't a burden? And the commandments to defending life are mitzvot. And what about those boys whom you are so opposed to, sitting on the borders and protecting you? This is not a mitzvah? We don't have an answer from the Chazon Ish. But what's fascinating is two things

Geoffrey Stern: here. Number one, I think the context of what Barak, the Supreme Court justice, said is this is not necessarily. And at the time, it was not necessarily taken as a timeless argument. They were talking about a particular time in Israel, where those students numbered 300 or 400. And so that was one thing that I think, go ahead.

Adam Mintz: With very little hope that that number was going to increase. Had you told the Chazon Ish that yeshivas would look like they do today. He would say, you're crazy. Impossible.

Geoffrey Stern: Let's hold on to that. I think that's a critical observation. The other thing is that Ben Gurion really argued, as Rabbi Kook or anybody, that what they were doing was an amazing commandment. It was settling the land of Israel. It was protecting Jewish lives. So that argument is with us even till today. And I would say if you had to characterize the argument of we have to act at a particular moment in time in order to save the whole yeshiva world that was destroyed in Eastern Europe, it would be a pasuk and a kind of a Talmudic guideline, which is eit la'asot. Most people talk about the first part, and then maybe they forget the second part. But it's a time to act for the Lord.

... And normally the translation is for they have violated the teaching. The way the rabbis took it is there are moments where you have to violate the law in order to keep the law. So, in Mishneh Torah, which is Maimonides, Maimonides talks about there are times where you have to abrogate the words of the Torah as a temporary measure. I think you could make the argument that the Chazon Ish was implicit in his argument that we only have three or 400 would-be yeshiva students. He might not have imagined what we have today, which is thousands and thousands. But he might have also said, the moment has passed. We have now established a yeshiva world; it's not going anywhere. Actually, there are more people learning Torah in yeshiva today than at any moment in Jewish history, as Maimonides says. They may not, however, establish the matter for posterity and say that this is the halacha. So this is the crux of the argument that we're having now. And especially, it's not a hypothetical argument, because as I said before, there are reserve soldiers who just can't carry the burden anymore.

..Right? I mean, that's for sure. And that Rambam is really interesting. When you start weighing mitzvot against one another, Ben Gurion said, we're also doing a mitzvah: we're protecting the land of Israel. They say, we're doing a mitzvah: we're studying. You know, there's also an issue of what we call in Gemara language, "how does it look," you know, when people are putting their lives on the line? Even if you think you're carrying a heavy burden, you need a little bit of humility to acknowledge the fact that you're protected, sitting in the beit midrash while they're putting their life on the line.

.. So I said in the intro, I quoted a rabbi who said something that must have smacked to all of us when we heard it as audacious. It says if learning Torah protected Israel, then what happened on October 7? But the rabbi we're going to get to in a few seconds is a rabbi called David Leibel, and he has an institution called Achvat Torah, and he's Haredi. So rather than quote all of the people, and I have quotes from Rabbi Riskin and others about everybody should serve, what we are seeing now is a moment—and the reason I bring it up now is you talk about how other people are looking at the Haredim. Here is a Haredi who says, how can you look at the mirror? That is the seismic change that is happening. He is making an argument, and we're going to kind of dissect it, that for the Haredim.

And he actually, to his credit, says on October 8, there were Haredim who were pouring out of their houses, asking what they could do. This is not necessarily something that has to be imposed on them. They are looking at themselves and saying, where do I stand? And that's why I said in the beginning, maybe this is redefining what it means to be a Haredi. So, this Rabbi David Leibel, have you heard of him, Rabbi?

..Yeah, he's well-known now as someone who, from within the Haredi community, is arguing for serving in the army. It's a little like Rabbi Baumbach. There are some real pioneers, some very courageous rabbis within the Haredi community who are trying to change that reality, the facts on the ground.

.. I would venture to say that maybe the slight difference between him and Rabbi Baumbach is that Rabbi Baumbach is working with Netzach Yisrael high schools, maybe even Haredim. Here's a 70-year-old Jew with a long beard who went to Panevezh Yeshiva and has the capability in terms of his learning to argue with his peers. And when someone says to him, how can you say this? There's a 90-year-old Rabbi Shach, he says, you know what? I wasn't born yesterday; I'm not a kid, and I can read the same text that you can read. He's really making a philosophical argument at a very deep level.

I will also say there is a YouTube video that is included in the show notes that literally has masses of Haredim demonstrating outside of his house in the middle of the night. He is literally making some really large waves. But I think he's coming back to our sources, and I think what he's saying is that whatever happened in the past was an "eit la'asot laHashem" (a time to act for God). It was a momentary provision to preserve the Torah. Now we have to follow the Torah.

..I think that's absolutely right. That's an important distinction.

.. So as I said before, you know, he went to Panevezh Yeshiva. He also became a businessman. And what he's been doing for the last 10-15 years is making kolelim. These are studies where people who are newly married will not work for the first multiple years of their lives. Instead, they will earn a living being paid to study Torah.

What he introduced were kolelim that also had education for high-tech training. So, he's followed the modern, the national Zionists, in also arguing for having regiments and battalions in the army where they serve together, but they also learn together. He'sdir organizations, which have never been done for the Haredim. He has a lot of background in this, and you could say he's in the right place at the right time for this initiative. But he literally takes apart the arguments that the Haredim have made.

The main argument, as you said right from the get-go about the Levites, was the argument that them learning Torah is protecting Israel. He goes back to the Talmud in Sotah 21a, and there it's talking about how a Sotah, when she's being judged for being unfaithful to her husband, shall be protected. The funny thing is, Rabbi, if you look at it in context, it says she'll be protected by how much Torah she's learned. And then they go to say, scratch that... then by how much Torah her husband has learned. Okay, which is another podcast that we could do. But the point was that it's talking about how studying Torah, when one is engaged in it, it protects you. He says this applies to an individual. It never applied to the community as a whole. It never applied to the country as a whole.

So he goes to the trouble of dissecting the texts they are using to exempt themselves, and he's taking them apart. He says if Torah study protects the Jewish people, then Torah students are culpable for the events of October 7th and for the deaths of soldiers in the war. He has a very sharp tongue.

..I mean, you need to have a sharp tongue because you're responding to a group that is very, very strong and rigid in their denial of that responsibility.

.. And I think, getting back again to others, like Rabbi Baumbach, who are working inside of the system, he's taking the system on. When he makes a provocative statement like that, he is a Haredi, he's saying to the Haredim, it's false what you've been told by your leaders.

There's this word called "das Torah," which is what the leadership has told us. He says, I have das Torah too, and I am telling you it's wrong. This is just radical in terms of what's happening.

.. So, your point is a very interesting point. The fact that Rabbi Baumbach works within the system, and this Rabbi Leibel seems to be taking on the system. We were at dinner a few weeks ago with an Israeli, a religious Zionist, what we would call modern Orthodox Israeli, and he was upset when we talked about people who work within the system. He says, what are you going to do? You're going to change 10 people, you're going to change 100 people? You know how many soldiers there are, and how many reservists there are, and you want to work within the system? He said, you need to take on the system. So I think that's also a distinction and that also gives credit to Rabbi Leibel who's taking the system head-on.

Geoffrey Stern: I couldn't agree more. And then, I think the biggest argument that is being made, and this is an argument that doesn't have an expiration date. In other words, you could say the reason why yeshiva students aren't drafted was because there were only 400. The bigger argument is, for every Haredi that goes into the army with a kippah, I'll show you a Haredi that leaves the army without a kippah.

It's this question of exposing our traditions and our youth in this very segregated, isolated community in the army; it will be the end of us. And again, what he says is fascinating because he says we just have to deal with it. If we need to have our own battalions, if we need to have prayer times.

I went and visited a battalion. I have a video at the end in the show notes of a soldier, actually a commander, who was a Haredi, who went through four years of training. They have study hours, they have rabbis teaching them, they have a higher grade of kosher food. There are no women allowed on the base.

It's no excuse. They can be better Jews. Since when do we ever say you can't do a mitzvah? Because at the end of the day, Rabbi, what is this? It's a mitzvah. Ben Gurion said it. And guess what? So did the pesukim that I quoted at the beginning of the show. This is a mitzvah not in the sense of it's a good deed, it's a mitzvah in the sense it's a requirement.

Adam Mintz: I mean, the risk is not only to the charedim. Everyone has risks in the army, not just risks of life and death, but social risks. Everyone who serves in the army will say that they come out of the army different than when they go in. They're stronger when they come out.

So the idea that we need to, you know, to baby, so to speak, the haredim, that they're not allowed to have risks, that's just that I think that's a very immature argument.

Geoffrey Stern: And I will add to that there is a growing number of haredim who are leaving the fold. One can make the argument that one of the reasons they're leaving is they can't make a living. Serving in the army in Israel is tied to making a living. You can't get gainful employment unless you've done your time, so forth and so on.

The point is, you could make a case. This was the case I was trying to make before when you said, Marit Ayin, what will other people say? He actually says this. When you look in the mirror and you have eight kids at home and you're not gainfully employed, and you look outside and see soldiers returning from the front to wives and kids who haven't seen them, you look at yourself and say, this Haredi world might not be for me.

I think part of his implicit argument is that the haredim could lose people also by not joining the army, by not joining civil society. In the show notes, there is an interview I did with this Haredi. After three minutes of him telling what happened, I have to say, in the army today, especially in battalions like Netzach Yehuda, many of the haredim that are going into the army today are ones that aren't learning or ones that haven't been fitting in. They are being sent.

This one, when I said to him, after he told me his inspiring story, I said, you know, in a way, if you hadn't been in the army, you might not be religious anymore. He looked at me and said, religious? I might not be alive. I might be overdosed on drugs.

The first group of people from the Haredi community were those who were actually leaders. That says something about the potential. I saw an article, we're going to finish with this in Israel Hayom or I should say Times of Israel, about an atheist who set up, there's no better word, almost like a Chabad type of table in the middle of Bnai Brak. He's trying to convince people to be Chiloni, to be secular. People are smiling, not taking them that seriously.

But I think it's representative of what could happen. I think the Haredi community is going through a metamorphosis. Today, it's fascinating to watch, but I don't think you can read the verses that we read in this week's Parsha and not think in terms of this absolute commandment to serve in the people's army.

Adam Mintz: Remarkable. I mean, this is so important and, you know, the more Geoffrey people talk about it, the more important it is. Everyone needs to talk about this topic. Rabbi Leibel deserves a lot of credit. Rabbi Bombach deserves a lot of credit. There's no one simple solution to this problem.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah. I reached out to Rabbi Leibel. I don't know whether he speaks English, but I invited him to the podcast. I think there wasn't enough time because I only prepare a day before. But I think...

Adam Mintz: Did you get a response?

Geoffrey Stern: I did. There just wasn't enough time. So I think when we get to the story in Numbers, what is it, 20 something, Numbers 32? That gives us enough time to set out an invitation. We will revisit this issue either with Rabbi David Leibel or somebody involved in his organization. Stay tuned.

Adam Mintz: Fantastic. Thank you so much.

Geoffrey Stern: Shabbat Shalom and see you all next week. We have Shavuos. In the meantime, if you haven't listened to it, listen to Kibbutz Shavuos and Kibbutz from last week. All the best, chag sameach.