Rashi; Rabbi Shlomo haYizhaki, an 11th-century French rabbi, is unquestionably the preeminent Biblical commentator. We will argue that his commentary on the unfaithful wife (Sotah) and Nazirite found in Numbers 5-6 reveals fascinating insights into women's hair covering and societal norms. We will also explore Rashi's unique perspective as a father of four daughters and winemaker, examining his interpretation of "para" (disheveling hair) versus the common translation of "uncovering." The discussion delves into the historical context of women's hair covering, its evolution in different Jewish communities, and the interplay between religious law and cultural influences. As a bonus we’ll also touch upon the tradition of studying Chumash with Rashi every week. Shenayim Mikra, Echad Targum. שנים מקרא ואחד תרגום

Sefaria Source Sheet: https://www.sefaria.org/sheets/412925

On Spotify:

Key Takeaways:

- Rashi's interpretation challenges traditional views on women's hair covering

- Cultural context significantly influences religious practices and interpretations

- The evolution of hair covering customs reflects changing societal norms

The discussion centers on two key elements from the parsha:

1. The law of the Sotah (The suspected adulteress)

2. The laws of the Nazirite

The Sotah

(12) Speak to the Israelite people and say to them: Any party whose wife has gone astray and broken faith with him, (13) in that another man has had carnal relations with her unbeknown to her husband, and she keeps secret the fact that she has defiled herself without being forced, and there is no witness against her, (14) but a fit of jealousy comes over him and he is wrought up about the wife who has defiled herself—or if a fit of jealousy comes over him and he is wrought up about his wife although she has not defiled herself— (15) that party shall bring his wife to the priest. And he shall bring as an offering for her one-tenth of an ephah of barley flour. No oil shall be poured upon it and no frankincense shall be laid on it, for it is a meal offering of jealousy, a meal offering of remembrance which recalls wrongdoing. (16) The priest shall bring her forward and have her stand before ה׳. (17) The priest shall take sacral water in an earthen vessel and, taking some of the earth that is on the floor of the Tabernacle, the priest shall put it into the water. (18) After he has made the woman stand before ה׳, the priest shall bare the woman’s head וּפָרַע֙ אֶת־רֹ֣אשׁ הָֽאִשָּׁ֔ה and place upon her hands the meal offering of remembrance, which is a meal offering of jealousy. And in the priest’s hands shall be the water of bitterness that induces the spell. (Numbers 5: 12-18) JPS, 2006

Rashi's commentary on the Sotah passage reveals a nuanced understanding of women's roles and dignity. While the traditional interpretation focuses on uncovering the woman's hair as a form of ritual shame, Rashi takes a different approach:

ופרע. סוֹתֵר אֶת קְלִיעַת שְׂעָרָהּ, כְּדֵי לְבַזּוֹתָהּ, מִכָּאן לִבְנוֹת יִשְׂרָאֵל שֶׁגִּלּוּי הָרֹאשׁ גְּנַאי לָהֶן (כתובות ע"ב):

AND HE SHALL PUT IN DISORDER [THE WOMAN’S HAIR] — i.e. he pulls away her hair-plaits in order to make her look despicable. — We may learn [also gs] from this that as regards married Jewish women an uncovered head is a disgrace to them (Sifrei Bamidbar 11).

Notice that Rashi interprets "upara et rosh haisha" not as uncovering, but as disheveling or mussing up the woman's hair. His reference to “We may learn”, or “from here” מִכָּאן is actually, in my opinion, a reference to an alternative interpretation or one may hazard, even a sociological observation… that this verse is used (or misused) as a source of the social stigma associated with the uncovering of a married woman’s hair.

§ The mishna stated: And who is considered a woman who violates the precepts of Jewish women? One who goes out and her head is uncovered. The Gemara asks: The prohibition against a woman going out with her head uncovered is not merely a custom of Jewish women. Rather, it is by Torah law, as it is written with regard to a woman suspected by her husband of having been unfaithful: “And he shall uncover the head of the woman” (Numbers 5:18). And the school of Rabbi Yishmael taught: From here there is a warning to Jewish women not to go out with an uncovered head, since if the Torah states that a woman suspected of adultery must have her head uncovered, this indicates that a married woman must generally cover her head. The Gemara explains: By Torah law, (Ketubot 72a:19)

R. Yishmael said: From here (i.e., from the fact that he is to uncover her hair) we derive an exhortation for the daughters of Israel to cover their hair. And though there is no proof for this, there is an intimation of it in ואף על פי שאין ראיה לדבר זכר לדבר (Sifrei Bamidbar 1)

It is clear from both Rashi and the sources that he cites that the traditional sources are trying to (artificially) justify the mandatory covering of a woman’s hair with our Biblical text.

Rabbi Mintz points out: "Whether or not covering hair is biblical or rabbinic is basically the question of that Rashi... Is that a Torah derivation? Is that really what the Torah meant? Or that's the rabbis making it up based on what the Torah says?"

Rabbi Mintz provides fascinating insights into the historical development of hair covering for Jewish women:

• In Lithuania, wives of prominent rabbis didn't cover their hair.

• The custom changed in America due to the integration of Hasidic and non-Hasidic communities.

"Every culture had a different tradition," Rabbi Mintz explains. "And the wives of Lithuanian rabbis did not cover their hair."

This invites us to critically examine the foundations of religious practices and be open to reinterpretation.

It is also clear to me that if a woman is accused of infidelity it is more likely that she has been galivanting around town all “oisgeputzd” well made-up and with her hair seducingly coiffured. Having the priest muss up her hair, would be much more appropriate then have him remove her modest her headscarf, (aka tichel).

In modern Hebrew, Perua definitely means wild and unkempt hair, as every child who has read Yehoshua Perua (aka Der Struwwelpeter) would know.

Other biblical sources also clearly share this meaning:

(6) And Moses said to Aaron and to his sons Eleazar and Ithamar, “dishevel your hair.” and do not rend your clothes, lest you die and anger strike the whole community. But your kin, all the house of Israel, shall bewail the burning that ה׳ has wrought. (Leviticus 10:6) JPS translation

A modern-day scholar and posek (halachic authority) and friend of Madlik, Professor Michael Broyde provides a body of evidence that the real prohibition referenced in our verse is that a woman should not leave the house with her hair in curlers or otherwise unkempt.

Additional authorities focus on the linguistic ambiguity in the Hebrew word "per’iah," which is the word used in Numbers 5:18, the verse that is the basis for the prohibition. These authorities argue that, while a Biblical prohibition is involved, it is only for women not to go with their hair disheveled, which they claim is what the word per’iah means, rather than uncovered; see Magen Avraham, commenting on Shulhan Arukh, Orah Hayyim 75:1 (#1-3); Yad Efraim commenting on id.; Peni Moshe, commenting on Even Ha’Ezer 2 1:2 (in Mareh Hapanim #2); Rabbi A. Hoffer, "Which Disheveling [Uncovering] of Hair for Women is Biblically Prohibited?,” Hazofeh Lehakhmat Yisrael 12:330 (1928); see generally Rabbi M. Kasher, Divre Menahem, Orakh Hayyim 5:2:3. (see: Further on Women’s Hair Covering: An Exchange, Tradition, Modesty and America: Married Women Covering Their Hair, MICHAEL J. BROYDE) see also: https://www.torahmusings.com/2010/09/hair-wars-ii/

But we don’t have to go to the laws of mourning or the Shulhan Arukh to confirm this meaning. A few verses later in our parsha we get to the laws of the Nazarite.

(5) Throughout the term of their vow as nazirite, no razor shall touch their head; it shall remain consecrated until the completion of their term as nazirite of ה׳, the hair of their head being left to grow untrimmed. פֶּ֖רַע שְׂעַ֥ר רֹאשֽׁוֹ (Numbers 6:5)

As Rashi writes:

The meaning of the word פרע is over-growth of the hair; similar is (Leviticus 21:10) “He shall not let his hair grow wild (יפרע)”.So is this simply an alternative translation and interpretation, or is Rashi making a statement?

Which brings us to the next verses and the adjacent subject matter of the Nazarite and …. wine.

(1) ה׳ spoke to Moses, saying: (2) Speak to the Israelites and say to them: If any men or women explicitly utter a nazirite’s vow, to set themselves apart for ה׳, (3) they shall abstain from wine and any other intoxicant; they shall not drink vinegar of wine or of any other intoxicant, neither shall they drink anything in which grapes have been steeped, nor eat grapes fresh or dried. (4) Throughout their term as nazirite, they may not eat anything that is obtained from the grapevine, even seeds or skin. (5) Throughout the term of their vow as nazirite, no razor shall touch their head; it shall remain consecrated until the completion of their term as nazirite of ה׳, the hair of their head being left to grow untrimmed. (Numbers 6: 1-5)

(11) The priest shall offer one as a sin offering and the other as a burnt offering, and make expiation on the person’s behalf for the guilt incurred through the corpse. That same day the head shall be reconsecrated; (Numbers 6:11)

On verse 6:2 Rashi asks: “Why is the section dealing with the Nazarite placed in juxtaposition to the section dealing with the סוטה?

לָמָּה נִסְמְכָה פָרָשַׁת נָזִיר לְפָרָשַׁת סוֹטָה?

Rashi, quoting the Rabbinic sources writes: R. Eleazer ha-Kappar said, “his sin consists in that he has afflicted himself by abstaining from the enjoyment of wine (Sifrei Bamidbar 30; Nazir 19a).

The full text is even more powerful:

As it is taught in a baraita: Rabbi Elazar HaKappar, the esteemed one, says: What is the meaning when the verse states with regard to a nazirite: “And make atonement for him, for he sinned by the soul” (Numbers 6:11)? And with which soul did this person sin by becoming a nazirite? Rather, in afflicting himself by abstaining from wine, he is considered to have sinned with his own soul, and he must bring a sin-offering for the naziriteship itself, for causing his body to suffer. And an a fortiori inference can be learned from this: Just as this person, in afflicting himself by abstaining only from wine, is nevertheless called a sinner, in the case of one who afflicts himself by abstaining from everything, through fasting or other acts of mortification, all the more so is he described as a sinner. (Nazir 19a:5)

This can clearly be taken as a polemic against the ascetic (and chaste) Essenes and early Christians.

And now back to Rashi…

As the Feminist Rashi Scholar Maggie Anton writes:

While Rashi is justifiably famous for these [his commentaries], it is less well known that under his authority and that of his Ashkenazi colleagues, Jewish women in medieval France, including his daughters, enjoyed autonomy and status not to be seen again until the twentieth century. When most women were illiterate and the rare educated woman was one who could read the Bible, Rashi’s daughters knew Talmud so well that legend has one of them writing his commentary on Tractate Nedarim’.

Rashi had three daughters, Joheved, Miriam and Rachel, but no sons. These learned women each married one their father’s students and their sons continued in the family’s scholarly tradition as Tosafists (later Talmud commentators who often disagreed with Rashi). Joheved, the subject of the first volume of my [Maggie Anton’s] Rashi’s Daughters trilogy, and her husband, Meir ben Samuel, had four sons as well as two learned daughters. Their son Samuel (Rashbam) wrote commentaries on the Bible and Talmud, and while still in his twenties, he assumed leadership of Rashi’s yeshiva when his grandfather’s health declined. Joheved and Meir’s youngest child, Jacob, became the greatest of his brothers. Also known as Rabbenu Tam, he founded his own yeshiva and became the undisputed leader of Ashkenaz Jewry, presiding over a synod attended by hundreds of noted rabbis. Miriam married the Tosafist, Judah ben Natan, and one of their sons, Yom Tov, became Rosh Yeshiva in Paris and founded a rabbinic dynasty there. Their daughter Alwina is believed to be the grandmother of Dolce, the scholarly wife of Eleazar of Worms. Rashi’s youngest daughter, Rachel (also known as Belle Assez) and her husband Eliezer were the parents of Shemiah, another prominent French scholar, but their marriage ended in divorce. Rachel is credited with having written a responsa on a question of Talmudic Law for her father when he was sick. See: RASHI AND HIS DAUGHTERS: ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DARK AGES Maggie Anton or better yet, buy and read Maggie’s Trilogy!

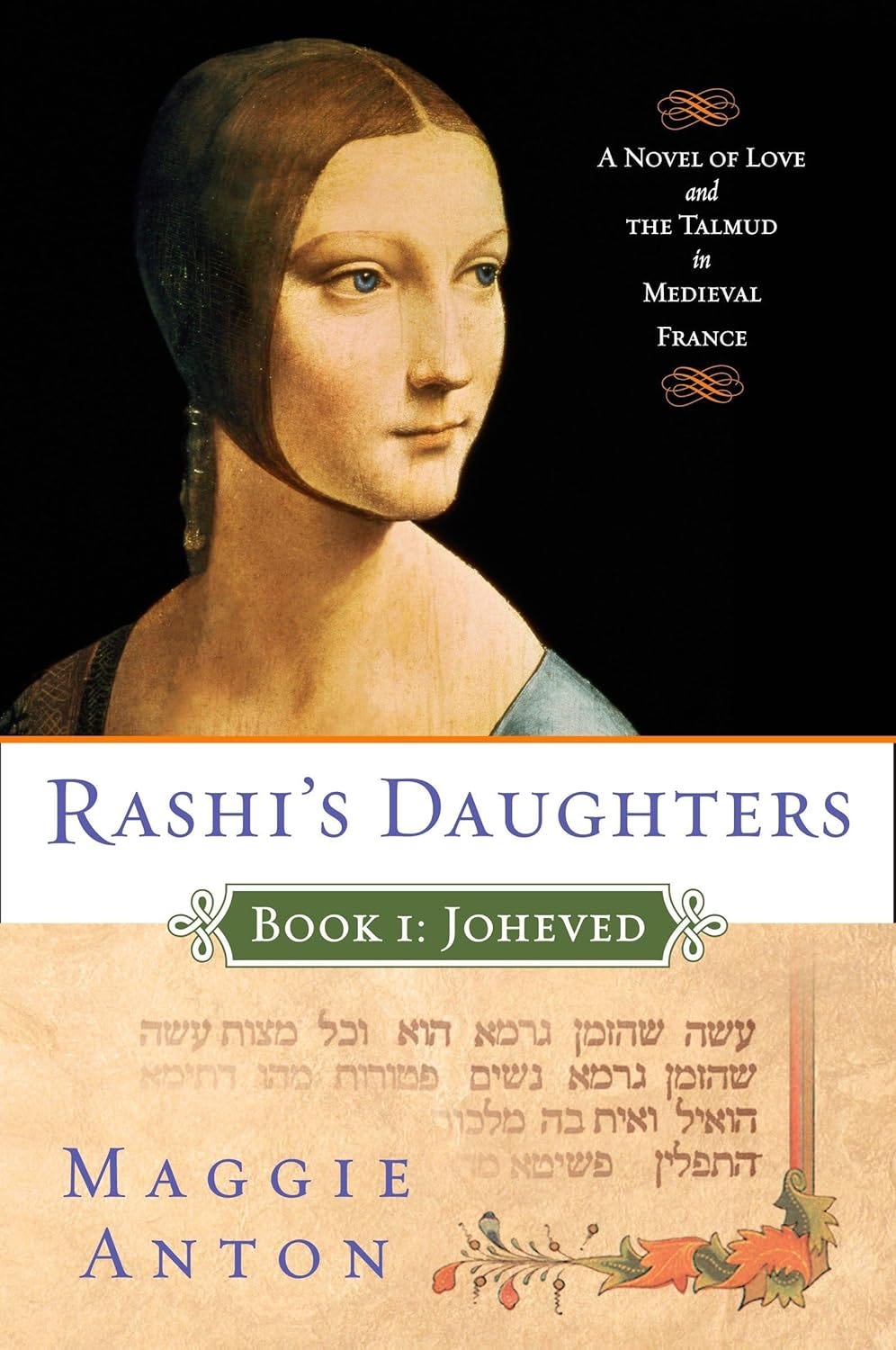

Rashi's Daughters, Book I: Joheved: A Novel of Love and the Talmud in Medieval France (Rashi's Daughters Series) Paperback – July 31, 2007

And as for Rashi being a fellow lover of wine and the legend that he earned a living as a Vintner… for some of use, a legend or even an urban legend with regard to love of wine may be enough. For others proof is necessary…

as the legend of Rashi the vintner is, Haym Soloveitchik, a professor at Yeshiva University and the leading contemporary historian of Halachah, or Jewish law, argues against it. In his 1978 essay “Can Halakhic Texts Talk History?” Soloveitchik argues that: “Jewish communities were generally tiny, averaging from a handful to a score of families and tended (in the Champagne region) to make their own wine… [which] was usually produced anew every fall… It is difficult to see how this could have been accomplished without the concerted effort of the entire community.”

Thus, he argues in a footnote, Rashi’s clear familiarity with wine production — as evidenced by his Jewish legal writings and Talmudic commentary — owes more to his having been a posek (a halachic decisor) for his small community, than to the prospect that he actually earned his living through wine.

As Soloveitchik put it, “the presumption is against anyone being a winegrower in Troyes” because the “deeply fissured soil to this day is inhospitable to viticulture.”

He allows that Rashi’s wording at times implies that there were some privately held vineyards, but almost certainly nothing productive enough for a family to earn a living off its wine.

“Despite all this,” Soloveitchik concludes, “Rashi may have been a vintner; but by the same token he may have been an egg salesman.”

see: https://www.washingtonjewishweek.com/what-kind-of-wine-did-rashi-make/

I say to Rabbi Hayim Soloveitchik (who I greatly respect), have another glass (or two) of wine and … join the team!

—

As for the custom to Read scripture twice and Rashi once, every week, Shenayim Mikra, Echad Targum, I think that the above shows how Rashi’s ability to cull our tradition and curate by reference of a simple textual gloss., our thoughts and discussion is the best endoresement. L’Chaim!

—

Transcript:

Geoffrey Stern: Welcome to Madlik. My name is Geoffrey Stern, and at Madlik, we light a spark or shed some light on a Jewish text or tradition. Along with Rabbi Adam Mintz, we host Madlik Disruptive Torah on Clubhouse every Thursday at 8 pm Eastern and share it as the Madlik podcast on your favorite platform. Join us today as we read about the unfaithful wife and the sober Nazirite through the eyes of the iconic Torah commentator Rashi.

Keep in mind that Rashi was the proud father of four daughters. He had no sons and had a day job as a winemaker. Does this affect his commentary? Grab a glass of wine, and let's discuss Rashi, women, and wine. L'Chaim.

Well, welcome to Madlik. I feel like Shavuot is over. We've all received the Torah, so we should all be excited to tackle the Torah this week. And before I even begin reading the text of this week's Parasha, you know, there's a lot being said today about Daf Yomi. Everybody is taking in Daf Yomi. But I think, and Rabbi, you can correct me on this, probably the earliest tradition of doing something where everybody did it, and I'm not saying just reading the Parasha, is something called Chumash and Rashi, where by every Friday you had to go through the whole Parasha and read it, not only the text but through the eyes and with the commentary of Rashi. Is that true?

Adam Mintz: So I'm going to tell you an amazing thing, which actually Sharon knows much better than I do. You know, printing started around the year 1450. We know that the Gutenberg Bible was printed before that. Everything was handwritten. And the first Jewish book that was printed in history, around 1470, was actually Chumash with Rashi, which I guess is not surprising. That supports your claim.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah, I mean, I know, and I'd love you to confirm this, too, that because of that, so much of how we read the text is colored by the lens of what Rashi brings. And he doesn't always. And we'll see this week; it's not as though he makes things up. He just is very selective in the texts that he brings to the table, so to speak. Therefore, you see the text of the Torah through the selection that Rashi makes.

Adam Mintz: Right, there's no question. I mean, you know, when you go to yeshiva, sometimes you're not even sure what's Rashi and what's the Chumash itself, which is a funny thing. Like, you say something, you say, "Doesn't the Torah say that?" Say, "No, that's Rashi who says that."

Geoffrey Stern: That's true. And I have to say, personally, I went to a yeshiva called Be'er Yaakov, which was in a little town called Be'er Yaakov. The head of the yeshiva was Rav Moshe Shapiro. But the real star was the Mashkiach, someone named Rav Shlomo Wolbe. He made the yeshiva study Chumash and Rashi for 15 minutes every morning.

He also took one student every year to study Chumash and Rashi with him, and I was fortunate in my second year there to be his chavrusa, his study partner.

Adam Mintz: Wow, that's amazing.

Geoffrey Stern: It is. And, you know, I don't even know how many things I've seen now through the eyes of Rabbi Wolbe, seeing through the eyes of Rashi, but it's powerful. So, anyway, this week is Numbers 5, and the name of the parasha is Naso. It talks about the unfaithful wife—say it—unfaithful in quotation marks, maybe yes, maybe no.

It says in verse 12, "Speak to the Israelite people."

Geoffrey Stern: And say to them, any person whose wife has gone astray and broken faith with him, in that another man had slept with her, unbeknownst to her husband, and she keeps secret the fact that she has defiled herself without being forced, and there is no witness against her. But a fit of jealousy comes over him, and he is wrought up about the wife who has defiled herself. That's one instance.

Here's another instance: Or if a fit of jealousy comes over him and he is wrought up about his wife, although she has not defiled herself. So that is the law of the Sotah. And it's not even clear whether she, in fact, was unfaithful. That party shall bring his wife to the priest, and he shall bring as an offering for her one-tenth of an ephah of barley flour. No oil shall be poured upon it, and no frankincense shall be laid on it.

Geoffrey Stern: For it is a meal offering of jealousy. I mean, when we were studying Leviticus, we talked about sacrifices as really just a way of religion and our tradition helping people in different moments. And we knew about sacrifices, sacrifices of sin offerings and thanksgiving offerings. Here we have a jealousy offering. It's a meal offering of remembrance, which recalls wrongdoing. It's not clear whose wrongdoing.

The priest shall bring her forward and have her stand before God. The priest shall take sacred water in an earthen vessel, and taking some of the earth that is on the floor of the tabernacle, the priest shall put it into the water.

Geoffrey Stern: After he has made the woman stand before God, the priest shall bare the woman's head and place upon her hands the meal offering of remembrance, which is a meal offering of jealousy. And in the priest's hands shall be the water of bitterness that induces the spell. So then, there is so much to discuss here. Sometimes I wonder whether we'll have something to discuss next year.

In the case of the Sotah, I don't have that issue. There's, and I've kind of referenced some of the areas that trigger my interest, but I want to speak today about one area where Rashi seems to feel very strongly, and the tradition, the text, and the translation of the text is almost uniformly against him.

Geoffrey Stern: And that relates to a very small part of what goes on. It says, "The priest shall bare the woman's head and place upon her hands the meal offering." The words in Hebrew are upara et rosh haisha, and para is the key question in Rashi. It says he shall put in disorder the woman's head. He pulls away her hair plates in order to make her look despicable. And then he goes on to say, we may learn from this.

As regards married Jewish women, uncovering their head is a disgrace to them. He says in the Hebrew Mikan, from here. So he's almost saying two things. The one thing is he's not translating it as uncovering the head. And so we should learn nothing about uncovering the head. And then he says, but this is what they learned. This is the source of the tradition that Jewish women have to cover their head. Rabbi, what's your read on this?

Adam Mintz: Well, which piece? I mean, the last piece, which is the piece that, you know, that the women have to cover their hair because the Sotah had her head uncovered. That's really an amazing kind of derivation because it's not a derivation that has anything to do with Sotah. It's a derivation that you see from the story of Sotah that women must have covered their hair because it says about the Sotah that her head is uncovered.

Geoffrey Stern: If that's the correct translation.

Adam Mintz: Right? That's right. That's what's interesting.

Geoffrey Stern: The interesting thing for me is, if let's go with the translation, it says uncover her hair, it's kind of like I do something wrong, and the rabbi takes off my kippah. Because what we're saying is that it's a sin for a woman. It's a disgrace for a woman to have her hair uncovered. It's against the law. And here we're making the woman break the law further.

I mean, that's one thing that's kind of strange about it. Would be much more, I think, straightforward to say that this woman appears, and she has maybe a cheap look about her. And maybe the husband is. She looks like, to everybody, like she's a little bit of a player.

And the rabbi dishevels her hair. He makes her look less attractive. And that's, I think, where Rashi is coming from, where he says he musses up her hair, he disorders her hair. It seems to be much more natural. And I think what Rashi is bringing into the discussion, you said it yourself, is there's no relation, really. It's a forced relationship between this custom or law that we have of women having to cover their hair and learning it from a Sotah. That's also the kind of challenge. And you kind of read maybe, maybe I'm reading into Rashi where he says the two things. He gives the correct translation in his mind, and then he says, "mikan l'bnot Yisrael Here's where they learn this. He doesn't say, this is where we learn it. It doesn't say, this is where the source is. He does seem to follow what you were implying, which there's a disconnect here, that they're almost pinning it on this peg, and it doesn't quite belong here.

Adam Mintz: I think that that's exactly right. I mean, I think that's interesting in Rashi. That's interesting just in the rabbinic tradition. You know, the whole... Let's go back to the story. The woman is suspected of committing adultery. She doesn't—we don't know she committed adultery. Basically, when we were young, we would say that we saw the wife of somebody with a man and a Howard Johnson's, right? They were having an ice cream together. But it looked suspicious. And the husband warns her, "I don't want you having an ice cream with this guy anymore." And she doesn't listen. And two witnesses see her having an ice cream again with the guy. Then the husband has the right to take her to Jerusalem and to find out whether or not she committed adultery. Now, the story, the way the Torah presents it, suggests that the very act of being suspected is itself an embarrassment, even if she turns out to be innocent. Even if it turns out that she goes to Jerusalem, she drinks this water, and nothing happens to her, it's embarrassing that they even suspected her. And I think that's interesting. That's part of it. He messes up her hair. He makes her look disheveled because she is supposed to be embarrassed because wives were not supposed to be suspected of adultery. Even if they didn't actually commit adultery, they weren't supposed to be in a way that gave the suggestion that they had committed adultery.

Geoffrey Stern: So, yeah, I totally agree with you. What I found fascinating is I am going to quote three more verses where Rashi gives the same translation of being disheveled or not looking your best. And the standard English translations across the board, I looked at pretty much all of them, keep to this, "baringyour head." So in Leviticus 10:6, right after two of Aaron's sons are sacrificed, killed by bringing this strange fire, it says in verse six, "And Moses said to Aaron and to his sons Eliezer and Itamar..." And now I'm reading the JPS translation, "do not bare your heads." And then if with an asterisk, it says, "dishevel your hair and do not rend your clothes, lest you die, and anger strike the whole community." So here, what he's clearly telling the family is, "don't go into mourning. Don't look like you're mourning." Maybe it's because God was the one who punished them, maybe because they're kohanim, who knows? But Rashi says, "al tifu'u" means "let not your hair grow long." And he says, "and from this, the Torah learns that when you mourn, you don't cut your hair." And of course, the reason why you do that when you mourn is you don't focus on your looks. You don't focus on the superficial when you're in mourning. So it, again, as long as we're dealing with Rashi, he does use this kind of same language. "Mikan, from here we learn avel asur be-tis po'et," that avel, a mourner, is not permitted. But what kills me is why you almost feel a tension between the standard translations. They keep on talking about uncovering your hair, which makes no sense in this context.

Adam Mintz: Well, I mean, the first question is that Rashi there, the sons of Aaron, translates the word tiferet para in a different way, which is "let your hair grow long." Unless you say that letting your hair grow long means make your hair disheveled.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah, I mean, I think it might.

Adam Mintz: Be the same translation. Right?

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah, no, I think he's consistent. He's like saying forget about your haircut, forget about your hairdo, or you do, you know. And so obviously in the case of the Sotah, you can't let your hair grow long in one hour. And that's even the case of the two sons. But they're going to be watched for the next 30 days or next year. So they should not go into this modality of letting their hair grow long. They should make sure to comb their hair is what it's saying. But again, he's consistent here and even in our parsha. Later on, we're going to get to the story and the law of the Nazirite. In Numbers 6, part of our portion, it says, "Throughout the term of their vow as a Nazirite, no razor shall touch their hair. It shall remain consecrated until the completion of their term as Nazirite of God, the hair of their head being left to grow untrimmed." So here everybody translates "para sarosho" as letting your hair grow, letting your hair out.

Adam Mintz: Right, so, so, so there they're definitely consistent.

Geoffrey Stern: Yes. But again, Rashi won't let it go away. So the Rashi over here says the word para is punctuated. And he says the meaning of the word para is overgrowth of your hair, similar to Leviticus 21:10, "he shall not let his hair grow wild." And he goes on. He, he's, he's... So I don't know whether he's fixated on this or not. I think that would be ascribing to him a little much.

Adam Mintz: Fixated on it. I mean, he's just, he's kind of consistent every time it comes up.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah. And he, and, and, and he points it out and he connects again, it seems to me that the, the, the text, the traditional text that puts this concept of a women needs to cover her hair on this is a little bit of, of a stretch because it's not only disconnected from the act that's going on, it also is not in line with the true meaning of the word. So it's a kind of a double stretch. In the Sifrei on Bamidbar, it is a source for what Rashi is talking about. And it says, Rabbi Yeshmael said, from here, from this verse that we have in the Sotah, from the fact that he, the Kohen, uncovers her hair, we derive an exhortation for the daughters of Israel to cover their hair. And though there is no proof for this, there is an intimation of it. So "Sh'eyn Raya le-dovar zacher le-dovar." So one thing we always point out on Madlik is how important sources are to all the commentaries at every level. No one, even if they try to massage the text a little bit and put later day custom into the earlier text, they point it out. It's very important to give the provenance of Halacha. And even the ones that say, "we learn it from here," they're only saying it's a Zacher le-dovar. It's kind of... I don't know, how would you translate?

Adam Mintz: Means that there's kind of a hint to it, but it's not a real source of interest.

Geoffrey Stern: It goes on and it follows this concept of what we're trying to do is to make her look less pretty. So Rabbi Yehuda says if her top knot were beautiful, he did not expose it. So he's saying if her hair is. And if her hair were beautiful, he did not dissemble it. If she were dressed in white, she is dressed in black. So the point is that we're definitely trying to take away from her beauty.

Adam Mintz: And if you understand the psychology, of course, the theory is that if she committed adultery, it's because she made herself beautiful to attract the man, and therefore the punishment is to dishevel her. So it's not just out of nowhere. That's the punishment for this sin.

Geoffrey Stern: Yeah, yeah. And then Rav Yochanan says something. Rav Yochanan Ben Baroka says the daughters of Israel are not made more unattractive than the Torah prescribes. "Ein menavalim benot Yisroel yoter mi ma she'katuv b'Torah." So again, there is a little bit. The Rabbis discussed everything under the sun, even fashion. And in this particular case, they were well aware of all the fashion and signs of beauty and stuff. So let's talk a little bit about your sense of a woman covering her hair. You spoke at the JCC about the history of conversion. What in your mind is the history of this covering of the hair?

Adam Mintz: That's a good question. Clearly, there is a history. Means clearly, the rabbis had an idea that women were supposed to cover their hair. What's interesting is that Maimonides says that it's not only for married women; any woman over 3 years old has to cover her hair. Now, tell me that's not unbelievable. Any woman over three years old. Maimonides presents it like this. Maimonides presents it that just like a woman has to be dressed, her elbows are not allowed to show and her knees are not allowed to show, so too, her hair is not allowed to show. That's Maimonides' view.

I think that today that's not our view. I think today the idea of wearing a hat is to identify a woman as being married. And if she's married, in a sense, she's off limits. It's kind of what we say is, you know, it's like sometimes some men wear rings and some men don't. They want to wear a ring to say, I'm married, I'm off limits.

Geoffrey Stern: So I think what you said regarding Maimonides is fascinating. I am no scholar in Islam. I do know as a tourist, so to speak, when I walk around in Islam, the women who cover their hair that are Muslim do it before marriage as well. And I wonder whether Maimonides wasn't affected by where he lived and that possibly, you know, in the Middle East in general, this was just the way women were dressed. And in a sense, we absorbed it and codified it.

But I do think that no one in the Muslim world who read what Maimonides wrote would have been surprised by that, because all unmarried women covered their hair. I mean, I think it would be almost radical for a Jewish woman to walk around with her head uncovered, even if she's unmarried, and be surrounded by Muslim women. That's correct.

Adam Mintz: I think that's 100% right.

Geoffrey Stern: Right.

Adam Mintz: Rambam was definitely influenced by the culture around him, no question about it. And I think we're influenced by the culture around us. You know, you would say 50 years ago, women did not cover their hair. Even very Orthodox women, very few women covered their hair. But now that's not true. Now, there are more Orthodox women, even, you know, not just Hasidic women who cover their hair. That's kind of, you know, tradition and the culture changes over time, and that's fascinating.

Geoffrey Stern: I'm sensing a real change. I was in Israel a month ago, and the number of Orthodox women that I met with, even I saw one on television during an interview. I did some. They're wearing turbans almost. These are, you know, I think it's almost taken upon women as something that is empowering, liberating, this concept of not objectifying my beauty or my femininity. But have you noticed also, I did a little research. There's something called a snood. There's a spitzel, there's a turban. When I grew up, there was a Sheitel I think Sheitels are probably falling away a little bit.

Adam Mintz: In Israel, but not in America. So I'll tell you, what you saw in Israel a month ago is very important. I know what religious community you come from by what type of head covering you have. Meaning, one type of head covering means that you're part of the Hasidic community. Another type says that you're part of the ultra-Orthodox, non-Hasidic community. The other says you're part of what they call hardal, which is kind of haredi dati leumi, which means that you're very Orthodox, but you're still a Zionist. Everybody has their own head covering. We went to visit somebody in a community, and literally, it was a Yishuv. Everybody in that Yishuv had the same head covering. Isn't that crazy?

Geoffrey Stern: Okay.

Adam Mintz: And that is, in this Yishuv, that was the rule. You weren't allowed to live in this Yishuv unless the wife covered her hair. If the wife went with her head uncovered, then you would be asked to move out of the Yishuv.

Geoffrey Stern: Did Rav Soloveitchik's wife cover her hair?

Adam Mintz: No, she did not. This is just interesting history. Lithuanian women didn't cover their hair. That was just a tradition. Every culture had a different tradition. And the wives of Lithuanian rabbis did not cover their hair. That was true about Rabbi Moshe Feinstein's wife. Now, when they came here to America, you see, America was a funny place because, you know, in Eastern Europe, Hasidim and non-Hasidim lived in different places. You know, a city was Hasidic, or a city was non-Hasidic. There was very little integration between the communities.

In a lot of places, there was competition between the communities. But they came to America. And because America was smaller, at least at the beginning, so there was, you know, everybody lived together. So the non-Hasidim took on some of the customs of the Hasidim, and the Hasidim took on some of the customs of the non-Hasidim. One of the customs that the non-Hasidim took on from the Hasidim is that even though in Lithuania the women did not cover their hair, in America, those, you know, those rabbis' wives covered their hair.

Geoffrey Stern: Neil, welcome to the bima.

Nachum (Neil) Twersky: So I prefer to be called Nachum. Technically, my name is Neil, and I just wanted to say that Rabbi Michael Broyd has a long, extensive, I would call it seminal article on the whole subject of covering one's hair from that perspective.

Adam Mintz: What's his punchline?

Nachum (Neil) Twersky: Well, first, the whole question is, is it min haTorah or miRabbanan? Okay, if it's min haTorah, as he suggests, according to some, it might be, then you're stuck. If it's rabbinic, then you can introduce what you might call, you know, the contemporary time. And it's open to rabbinic interpretation as such. He doesn't come out right and say it, but he infers that on that basis there might be some permission for women, you know, not to cover their hair. I think what he's trying to do in some way is objectify that which you refer to as what?

Rabbi Soloveitchik, I will tell you, since my sister asked whether she should cover her hair, the Rav told her, yes.

Adam Mintz: So that's interesting. So let me just tell you, actually, Geoffrey, this is all relevant to what we're talking about, because whether or not covering hair is biblical or rabbinic is basically the question of that Rashi. We're going back to that Rashi. And that Rashi says that we derive from this week's Torah reading that a woman needs to cover her hair. And the question is, what kind of derivation is that? Is that a Torah derivation? Is that really what the Torah meant? Or that's the rabbis making it up based on what the Torah says? And that's interesting, right?

So, it's really that whole discussion and, according to what Nahum said, the tradition today is really based on how you understand that Rashi. So it all goes back to our good friend Rashi.

Geoffrey Stern: Absolutely. In the source notes on Sefaria, I bring additional texts which literally start to distinguish between when, even those who believe it's from the Torah, when is it from the Torah? Is it in a totally public domain? And then, when is it a custom? When is it something that was from the rabbis? That would be courtyard to courtyard. So it's all there in the source notes. And now we have a new source as well. Thank you for that, Nahum.

We need to finish up, but I love the fact that we talk about what Rabbi Soloveitchik did and his wife, we talk about Nahum, your sister went to him. The fact, I think if we walk away from one thing, one of the amazing things about Rashi is that, I said this in the intro, he had four daughters and he had no sons. He had sons-in-law who became the Tosafot. And they had names like Rabbeinu Tam. They used to argue with their father-in-law all the time. If he said yes, they said no. But one of his daughters, Rachel, got divorced, and it wasn't because I think they were childless.

There are many people who believe, nothing is totally documented, that his daughters put on tefillin. One of his daughters, when he was sick, wrote his teshuvah for him, wrote his Kuntres for him. So these were clearly very learned. And doesn't it have to be that way? I mean, if you're a man of his knowledge and you have only four daughters sitting around the table, it's Yentl, isn't it?

And I think that without projecting onto him, but clearly in this case of the Sotah, this woman accused of this, he is suspected. He is taking a real stand in terms of what this means. And I don't think he's taking a strong stand in terms of the covering of the head. But in any case, he definitely has something to say about it.

I think it's a wonderful way to read the parsha with Rashi, get to know his daughters, get to know practice in the world that we live in. We always talk about the nomenclature, the vernacular in Hebrew. I have to mention a book that every kid reads when they grow up, and it's called "Yehoshua Perua." And "Yehoshua Perua" is about a kid with hair that is wild and grows very long. So another great way to...

Adam Mintz: That's a great way to finish up. We went full circle from Rashi to Rashi to a kids' book. I think that's fantastic.

Geoffrey Stern: Okay, well, Shabbat shalom to everybody.

Adam Mintz: Shalom everybody. Thank you so much. Enjoy the parasha. We'll see you next week. Be well.

Geoffrey Stern: Shabbat Shalom. Enjoy your Chumash and Rashi.